Instacart IPO: Harbinger of Doom?

Why one of the year's only bright spots should have late-stage mega-fund backers terrified

Instacart’s IPO last month made quite a splash, in large part as it is one of the very few venture backed companies to go public since the bubble burst in early 2022, and at nearly $10 billion, by far the largest (other than Klaviyo, which debuted a day later). While it has been widely lauded as a unequivocal success for the whole of the VC industry, things aren’t always what they seem, and in this case, we see a very distinct tale of two markets.

Courtesy of a detailed summary of each of Instacart’s venture funding rounds from Series A onward, provided in its S-1 (IPO prospectus) filing, we have a fairly unique opportunity to see not only the totality of venture returns, but returns by stage as well, and the results are fascinating.

By all accounts, Instacart seems to be a healthy company with good prospects. Analyst ratings are a bit of mixed bag (Yahoo Finance shows aggregate ratings sitting squarely between “buy” and “hold”), but the average analyst price target (also from Yahoo) is roughly 44% above today’s close (18% above the IPO price) and a quick glance at recent numbers shows good growth and relatively strong margins (both gross and operating margins are far better than most of the software companies that snuck through the IPO funnel in 2020 and 2021).

The returns were also outstanding for its early venture backers; for the rest, however, this looks to me like it might be the canary in an extremely toxic coal mine.

Unpacking the VC Returns

Overall

On its face, returns for Instacart’s venture backers in the aggregate looks like a solid win. In total, these shareholders invested $2.8 billion over 9 funding rounds1 and received cash or shares worth just over $5 billion in the IPO. On a weighted average basis, that comes out to an 11.8% IRR, outpacing the S&P 500 by 200 basis points per year.

Of course, venture LPs do not invest on a gross basis. When pro forma fees and expenses are taken into account2, the IRR for venture LPs drops to 7.6%, underperforming an S&P ETF (also net of expenses) by 220 basis points over the same period.

Does this mean that I — a venture manager myself — am telling you that you should abandon the sector and just invest in an index fund? Of course not!

These are blended venture returns and not all venture is created equal (or even close to equal in this case).

Late-Stage

The selling point of late-stage venture funds (at least according to late-stage VCs) is that they’ve found a sweet spot where LPs get the sought-after public market outperformance venture has long been known for, but with a much shorter holding period.

In this case, they delivered on half of that promise.

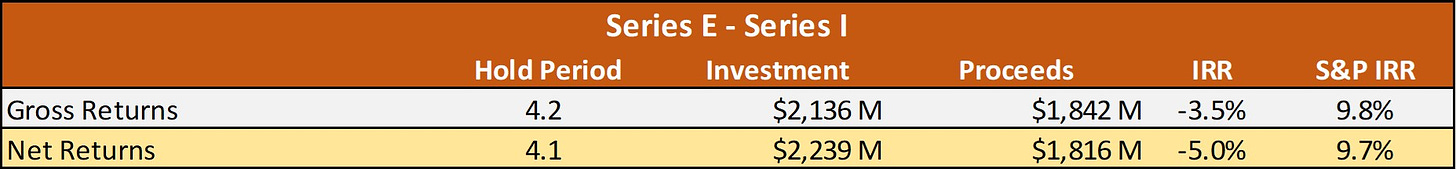

On a gross basis, the waited average holding period of Instacart’s Series E - Series I investors comes in at a little over 4 years (vs. 10 years for the Series A). Unfortunately for those who bought into this story however, they forgot about the returns. Aggregate gross returns for investors in these final five rounds was -3.5%. That’s right, the Series E+ cohort collectively lost money on one of the best IPOs of the past 2 years before accounting for management fees and expenses.

Net IRR for this contingent came in at -5.0%, resulting in an overall loss of 19% of LP capital over the 4.1-year weighted average holding period.

This wasn’t a function of one overpriced, outlier round in the bubble years, either. Investors in four of the five late-stage rounds (starting with Series F in 2018) lost money on a net basis, with the one profitable round (Series E) returning just over 4% annually (less than half the S&P over the same period).

As for the Series C and D rounds (the “growth stage”, I guess? I have trouble keeping track of the alphabet soup these days), they both showed positive net returns, though they were handily outperformed by the S&P (by 59% and 38%, respectively).

Early-Stage

To the good news! Took us a minute to get here, but I think you’ll agree it was worth the wait when you see the numbers.

We’ll skip right to the net returns, which were exceptional (fees, expenses, carry, and all). Looking first at Series A and B in the aggregate, we see a net IRR of 41.2%, versus 9.5% for the S&P over the same time period. This is the difference between a total investor return of 2.2x (S&P) and 22.4x (early-stage venture) on their investment.

Series A investors fared even better (by a wide margin, in fact), with a net IRR of 56.3% and a net total return of 81.7x, and Seed investors in Instacart likely saw net returns well in excess of 100x their initial investment (see footnote 1 for more on this)

The potential for returns as exceptional as these are what makes venture capital such an attractive asset class, and the reason that (unlike with hedge funds, private equity, and other private market asset classes) no smart LP even bats an eye at a 2 & 20 fee structure for an early-stage venture fund. You simply can’t get returns even close to this anywhere else (including late-stage venture).

The Canary in the Toxic Coal Mine

So, why am I declaring this one IPO a “harbinger of doom” for late-stage VC? After all, it’s just one exit; not exactly a robust sample size. Well, Instacart may be just one company, but it is the single best company in these late-stage portfolios. How do I know this? Because it’s the only one that’s been able to crack the IPO market!

Public markets are not egalitarian; it’s survival of the fittest, and if late-stage investors just lost more than $400 million on the IPO of the their fittest company, what does that tell you about the rest of their portfolios? Time will tell, but I think there’s a good chance that the late-stage funds of the 2020 and 2021 vintages (and perhaps a few of the years leading up to 2020) may end up being the worst performers in the history of the asset class.

It’s probably actually 10 rounds, as there is no Seed round listed in the S-1. My guess is the Seed was done as a SAFE or convertible note, which converted to Series A shares in that round. If so, the dollars invested and returned to seed investors are still included (via the Series A bucket), though their returns were probably another 1.5 - 2.5x that of those who first came in at Series A.

For the pro forma calcs, I used a 2% management fee, 0.35% annual expense ratio, and 20% performance fee. Obviously not all funds have the same cost structure, but as someone who runs multiple early-stage funds, I’m comfortable that we’re presenting a relatively accurate picture here.